How we designed a product from 0 to 1M€ in 90 days

How design became the engine behind alignment, clarity, and €1M in early revenue.

No, it’s not clickbait: we took a brand-new compensation product from launch to €1M in less than three months.

No growth hacks, no shortcuts.

Just a cross-functional team working with extreme clarity, with design acting not as the last step, but as the engine that aligned problems, systems, teams, and decisions.

Context about Factorial

At Factorial, we build tools that help companies run their day-to-day business across people, cash, and compliance.

Each new product is built by a dedicated team of engineers, designers, and product managers.

We invest around €0.5M per team, expecting that investment to double within a year.

Ambitious, yes, but repeatable.

And one reason it works is that design isn’t waiting for tickets. Designers shape the problem from day zero: discovering root causes, framing systems, envisioning solutions, and helping the whole team decide what matters.

Our last accomplishment: from 0 to 1 in 90 days

Employee compensation (Payroll) is one of the most painful processes for any company, and one we’d been trying to solve for years. But after multiple iterations built on top of an aging, complex system, we reached a point where progress meant starting over.

So last year, we rebooted the product completely.

Less than nine months later, the new version not only launched, but it also became the fastest-growing product in Factorial’s history.

Looking back, a few core practices made that outcome possible.

Here are the 7 keys that helped us build a product from 0 to 1M€ in just 90 days:

1. Looking beyond the obvious pains from different perspectives

Every problem has a champion: the person who feels the pain first-hand and would gladly pay to reduce errors and save time.

For employee compensation, the champion was the HR admin.

But problems rarely come from a single source.

For years, while trying to solve payroll, we assumed the main issue was the calculation process. Most visible errors came from there, so we tried to fix that.

Once we started asking better questions and talking with other stakeholders, we realized calculation was just a symptom.

Here, design played a key role: instead of stopping at the obvious pain point, we used user research and stakeholder mapping to expand the picture. We spoke not only with HR admins, but also:

Managers: who in many companies calculate extra hours, bonuses, and variables manually. We discovered chaos and inconsistency in how they tracked compensation.

External sources: like expenses, benefits, and payroll calculation tools.

Bookkeepers: responsible for calculations, working with very manual, error-prone processes.

Finance teams: who manage payments and forecasts, and often detect errors caused by all the previous steps.

Employees: who mostly don’t understand their payslip, and report “errors” that are actually tax nuances.

In this discovery work, ensure you:

Frame the right questions

Connect perspectives

Go from symptoms to root causes

Turn messy stories into a clear problem space

2. Shadowing customers like it was our first day on the job

Forget research playbooks that say a script is the most important thing.

Scripts are useful, but they also limit your ability to react. It’s easy to bias a script around your assumptions and miss what’s really happening.

I always give my designers the same prompt:

Go to the interview as if this is your job, and the person in front of you is doing a hand-off of their work. If you don’t understand it well enough to do it tomorrow, you’re out.

This mindset shift brings you from generic, high-level questions to end-to-end understanding.

In payroll, this helped us see:

How complex it was for some companies to track and calculate compensation across multiple tools

How HR admins had no way to know if managers’ calculations were correct

How painful communication with bookkeepers was, including email chains of 50+ messages for a single month

How disconnected HR and Finance teams often are.

So, your next customer interview, instead of investing hours in a rigid script, ask users to:

Walk you through their entire process

Share their spreadsheets (yes, everyone has a spreadsheet)

Show real examples

Expose the tools, hacks, and workarounds they use

3. Mapping the entire problem before anything else

The most human (and very designer) reaction is:

I see the problem, let’s design the solution.

Stop.

One of the biggest mistakes we made in the past 7 years was treating each pain point in isolation and designing local fixes. That’s how you end up with patches, not products.

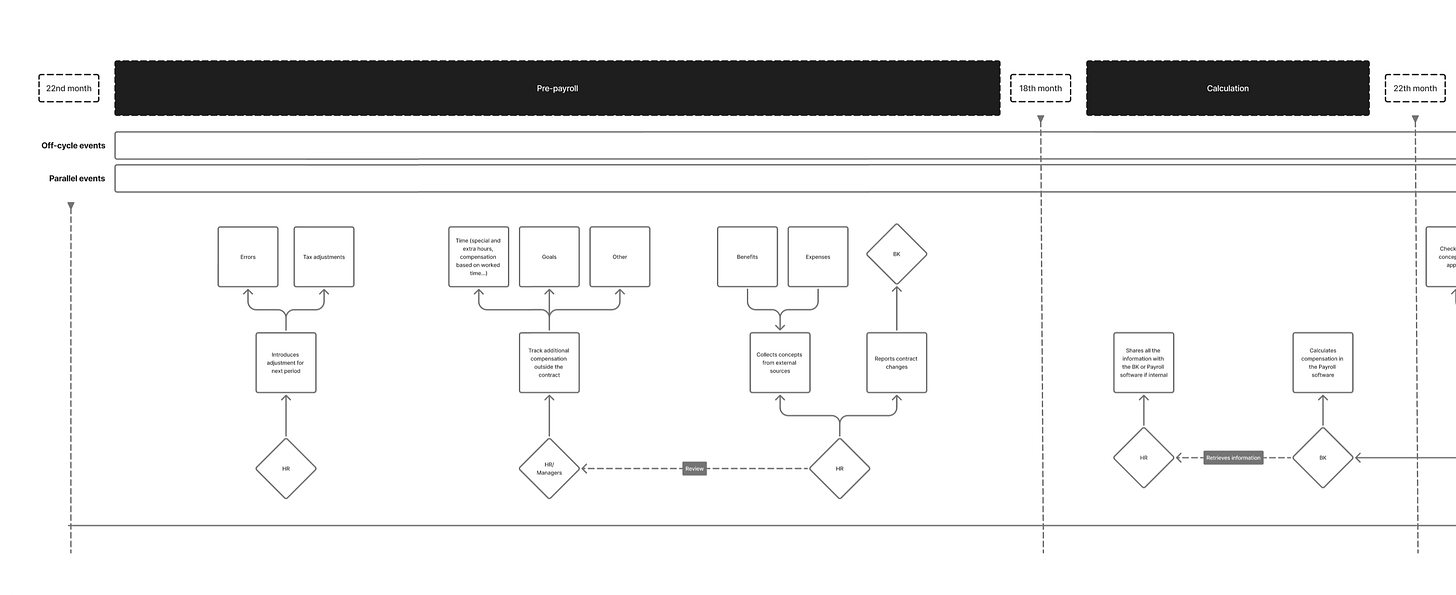

This time, we mapped the entire system:

from managers tracking extra hours and variables

to HR consolidating information

to bookkeepers calculating payroll

to finance managing costs and payments

to employees reacting to their payslips

With this map in mind, you stop designing features and start designing systems.

We often think “system” = design system.

But think about your home: electricity isn’t just a solution for your bathroom. It’s a connected system that powers the entire house.

Compensation works the same way inside a company, and so do most problems.

4. Exploring the end-to-end solution before defining the MVP

This is where designers have superpowers.

Our value is in connecting the dots to envision a simplified, end-to-end solution that actually solves the root problems.

Before jumping into an MVP, we forced ourselves to answer:

If we had all the time and resources, how would we solve this end-to-end?

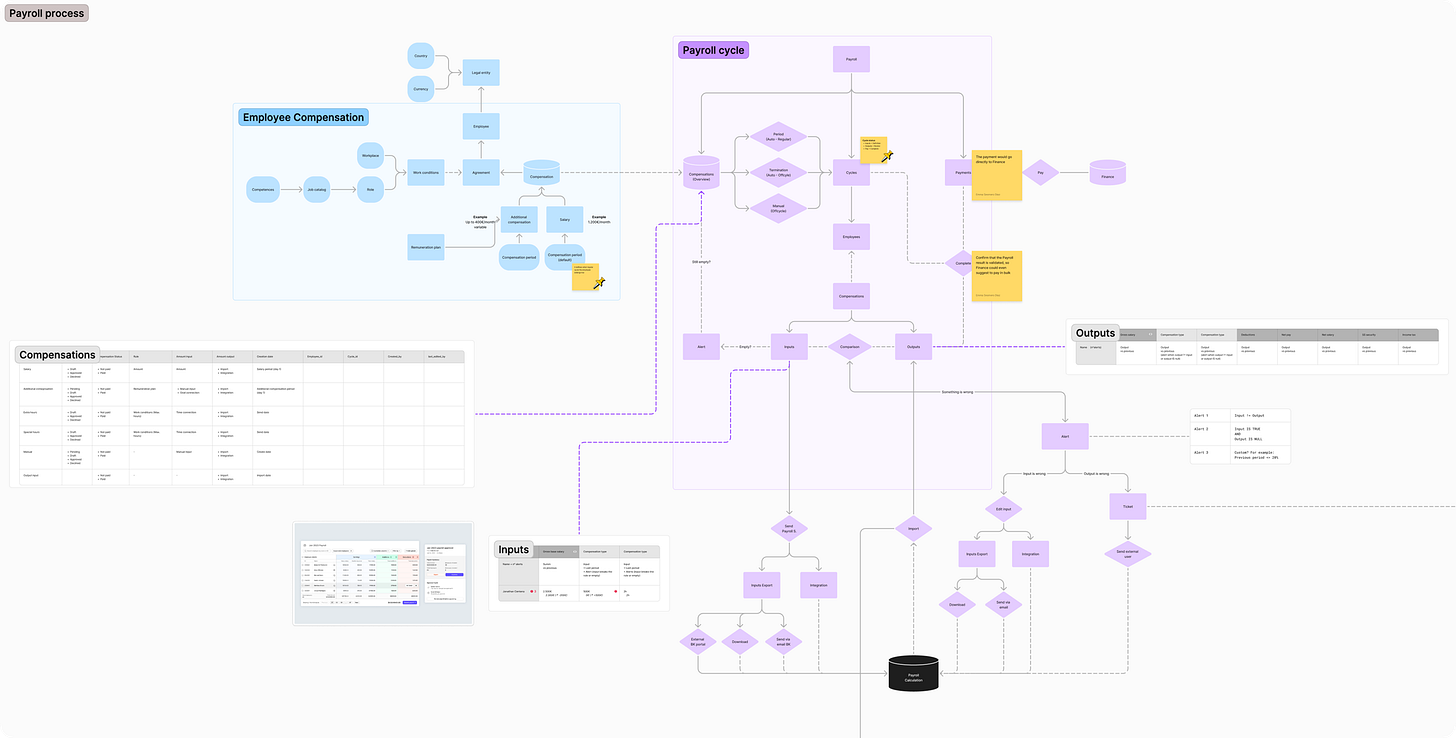

We started with diagrams: identifying the different pieces we’d need to assemble to solve the real system, not just one screen or one step.

In each iteration, we tried to:

Simplify the system, keeping fewer, more powerful pieces.

Ensure we were still solving the root problems, not just trimming complexity for the sake of elegance.

Design led this work, but it was a cross-functional exercise: PMs, engineers, and other stakeholders stress-tested the model. The diagrams showed that many pains were more connected than we thought, and that a single piece could remove friction for several users at once.

5. Visualizing the future early to align the team

Diagrams are great for reasoning, but people need to see the product.

We started creating Lovables to turn those diagrams into something more tangible: not final designs, but clear, visual stories of the future product.

This helped:

Align the team around a shared vision

Make it easier for non-designers to contribute

Trigger more concrete feedback and ideas from PMs and engineers

Once everyone could see potential interfaces, the conversation changed. Everyone can react to a UI.

Diagramming systems may be for a subset of the team; visualizing workflows through interfaces is for everyone.

When we had enough clarity, we moved from Lovables to more realistic flows in Figma.

Lovable wasn’t as powerful back then as it is today, but using it pushed us to imagine the solution inside Factorial, integrated with our existing products and flows.

6. Shaping an MVP that solved something real

I’m old-school: MVP still means Minimum Valuable Product to me.

That means:

A well-crafted experience

Limited functionality

Solving a meaningful problem

Ready to sell

Over the years, MVP has been downgraded to ship something shitty and random.

Also, when shaping our first MVP, we avoided a few traps:

Foundations-only MVPs: Foundations are important, but they don’t solve a problem by themselves. An MVP has to solve something concrete from day one. Design helped keep us honest: if a customer can’t feel the value, it’s not an MVP.

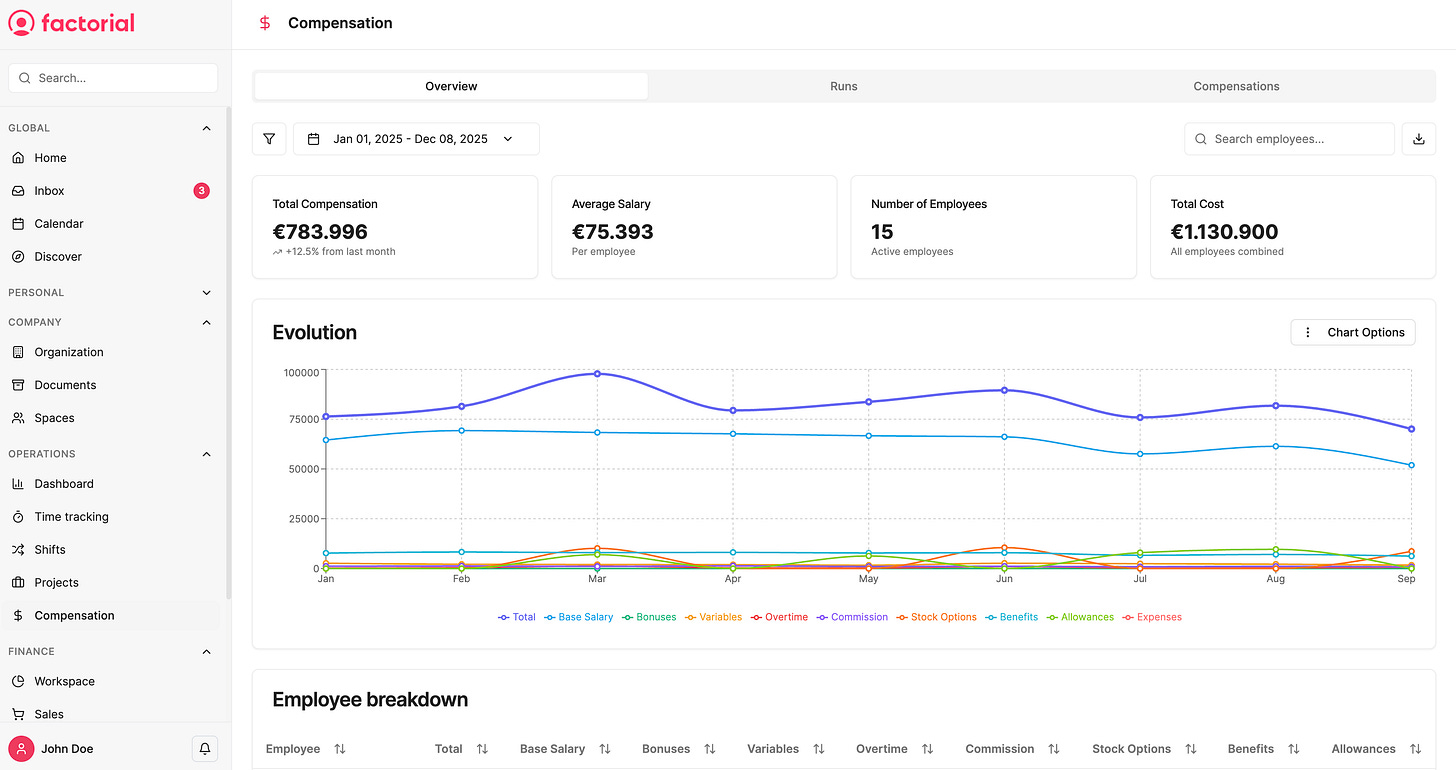

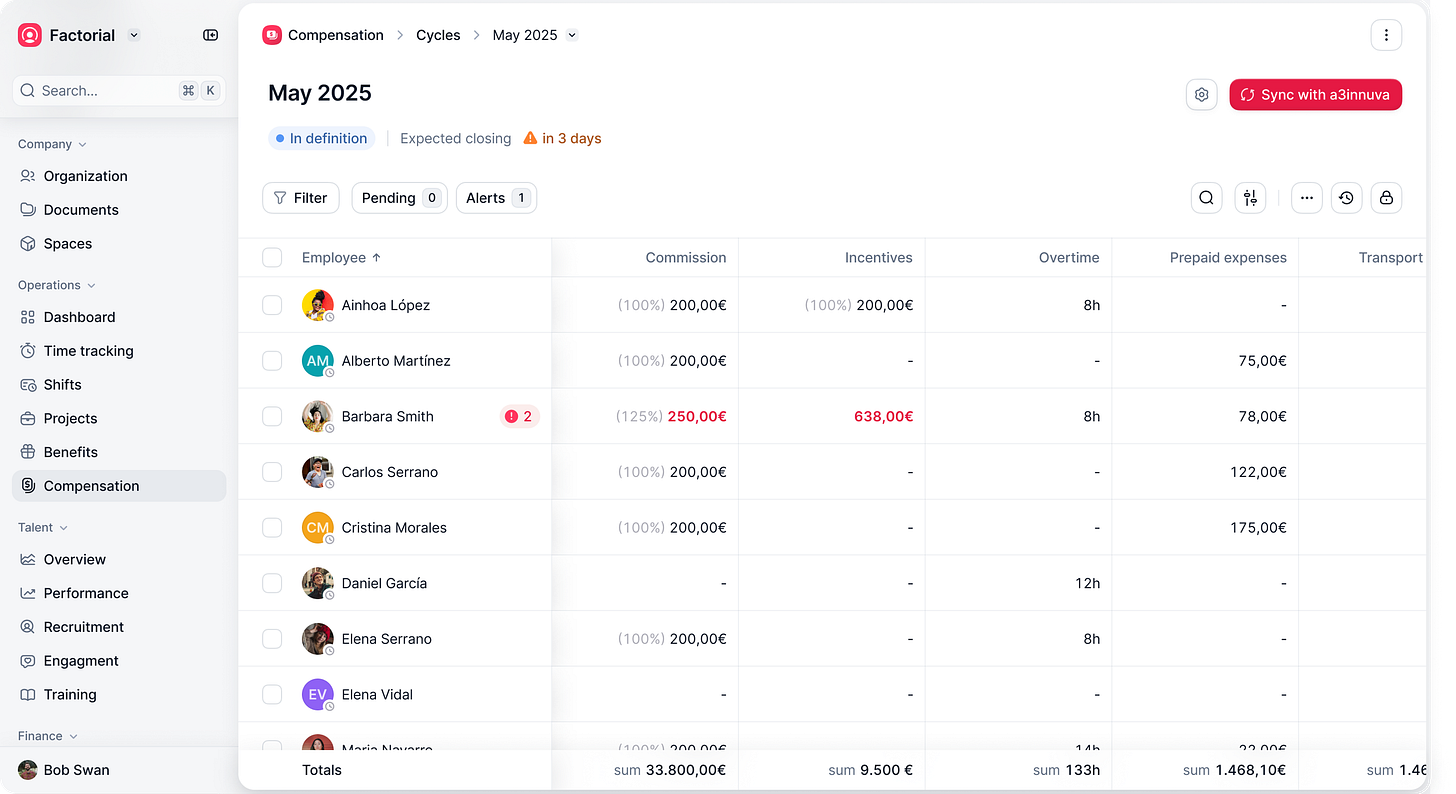

Only solving the biggest visible problem: Solving just the biggest problem isn’t enough when the experience is end-to-end. Instead, we chose to cover a thin slice across the whole journey: not perfect anywhere, but significantly better overall.

Designing for everyone (Global ICP): It’s almost impossible to design a good MVP for everyone on day one. We narrowed our ICP to companies where we could create value quickly.

For compensation, our MVP focused on Spanish and German companies with around 100 employees.

The solution covered a bit of each pain along the journey: managers’ data, bookkeeper communication, error tracking, and tools connectivity.

Design’s role here was to prioritize flows, not features.

7. Start selling before we’re done building

The only real validation is simple:

Are people willing to pay?

We started selling our Lovables and first vision before having the product.

We didn’t ask “Do you like it?” or “What do you think?”

Instead, we:

Placed customers in real scenarios from their own company

Walked through their actual process

Measured if we could save time, reduce errors, and cut costs

The answer was clear: some customers were ready to buy even before the product existed.

Here’s what worked for us:

Don’t wait for a finished product to sell. Sell the vision and the path there.

Avoid vanity metrics early on. NPS, CSAT, or usage patterns come later. Early on, focus on: time saved, errors reduced, money saved.

Use realistic prototypes. Lovable, Figma, or any AI tool, but make it feel real enough for users to imagine using it tomorrow.

Ask about outcomes, not opinions. Skip “What do you think?” and ask:

How much time would this save you?

How many errors would this avoid?

What would this mean in cost?

Design here becomes a sales asset: good prototypes and clear flows make it easier for sales and product teams to have serious, outcome-driven conversations.

Conclusion

Taking a product from 0 to €1M in a few months is not about luck.

It’s about:

identifying the right problems, not just the symptoms

understanding the full system around those problems

envisioning an end-to-end solution

shaping a focused, sellable MVP

and validating value with real customers as early as possible

Of course, there are other key factors at play, like market size, how painful the problem is, or how many competitors you’re up against.

However, in all of this, design is not decoration; design is how we:

discover the real work users do

turn chaos into clear maps

imagine better systems

make them tangible through prototypes

and help the whole team pull in the same direction.

Without design, problems stay as symptoms, and solutions stay as features.

With design, a cross-functional team has a shared language to build products that actually move the needle.

If you look at your current product, where would letting design lead earlier have made the biggest difference in going from 0 to 1?